Value-based payments for providers are gaining momentum in the United States. Pharma and Biotech manufacturers, as well as other players in the ecosystem, must recognize how this changes provider incentives and behavior, and adjust accordingly.

The US healthcare system has long struggled with significant costs without a corresponding improvement in public health metrics. The US underperforms in a variety of public health metrics, yet spent 16.9 percent of GDP on healthcare in 2018, twice as much as the OECD average.

Part of the problem lies in the current dominant payment structures and the perverse financial incentives they create for providers. To give three examples that illustrated this even before the pandemic:

- Fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursement, which underlies most payments to providers, can perversely incentivize them to maximize both the rate charged for services (through negotiations or potentially through optimizing their patient/payer mix), as well as through the total volume of services provided. From diagnostic tests and primary care visits, to MRIs and specialty IV infusions, providers can find themselves under pressure to continually deliver incremental volume to maintain revenue growth for their organizations.

- Dialysis providers have struggled with Medicare rates have not kept up with the cost to treat, leading to an overdependence on Commercial rates that are two to three times higher to stay profitable.

- Similarly for Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNFs): Short-term post-acute care is reimbursed under Medicare Part A at a higher rate than reimbursement for long-term stays, which is typically paid by State Medicaid programs. This has introduced a perverse incentive where SNF operators lack a financial reason to prevent hospitalization of long-term stay patients – the patient’s stay after their return can be billed under Part A for some time.

The pandemic has further compounded the challenges above as providers must now manage additional operational complexities, inflation impacting prices of basic supplies, and a broad staffing shortage.

To address the challenges associated with existing payment models, payers and policymakers are increasingly looking to adopt new provider reimbursement models that reimagine the US healthcare system by repurposing financial incentives to reward improved health outcomes while limiting waste and unnecessary care.

A good first try: Bundled payments

To address increases in costs, payers first started on the path towards value-based payments with the introduction of bundled payments.

Bundled payments were conceptualized as early as 1983, and have also been implemented by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) through Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) for joint replacements, acute, and post-acute care, as well as (in some sense) for primary care through Medicare Advantage.

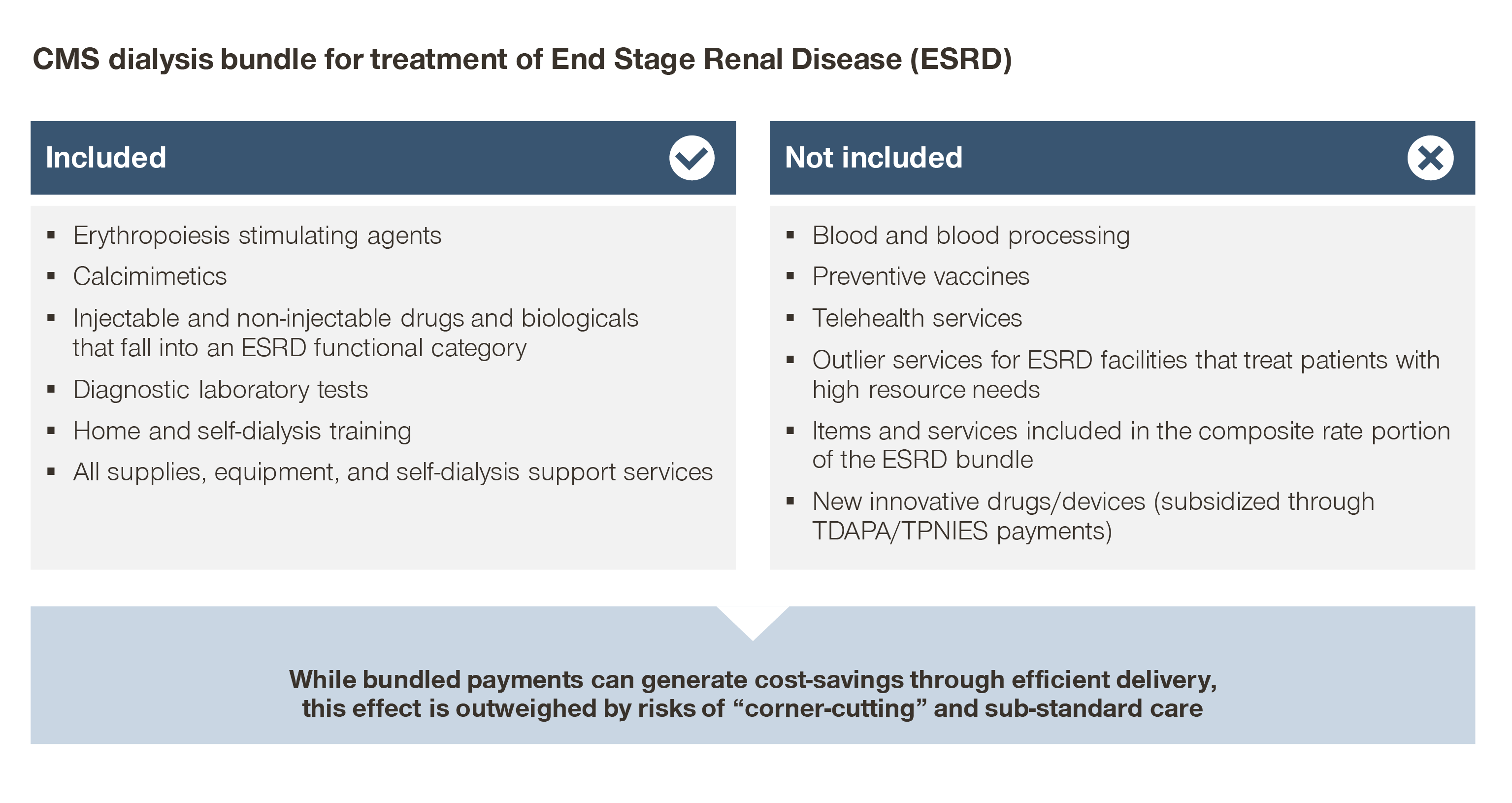

Fundamentally, this shift attempts to expand the definition of “service” in a FFS construct, by bundling many individual services together under one payment. This provides a previously non-existent incentive to efficiently use resources (devices, drugs, equipment, etc.), which are included under the bundled payment.

When providers are at risk for the costs of providing the service, they retain a greater operating margin by reducing spend. However, bundled payments still have their issues, primarily driven by retaining some misaligned incentives from FFS reimbursement:

- Despite incentivizing efficient resource use within the bundle, bundled payments do not incentivize clinically rational use of the overarching bundled service nor do bundled payments necessarily incentivize reduction in total cost of care

For example, Medicare payments for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) have been bundled since 2011, yet spend continues to increase disproportionately to the overall Medicare population.

While bundling dialysis payments incentivizes efficient delivery of those services, bundling payments by itself does not incentivize avoiding or delaying progression to ESRD in the first place.

Focus instead is placed on driving profits: maximizing chair utilization and patient volume (and therefore maximizing reimbursement from CMS/commercial payers), and minimizing costs (efficient operations, competitive tenders, etc.). Bundles by themselves are only the first step toward value.

- Similarly, bundled payments can drive down the use of costly therapies within the scope of that given payment, potentially at the cost of downstream complications

For example, the use of erythropoietin-stimulating agents were halved after CMS introduced bundled payments to ESRD. While fixed per patient reimbursement drove down the use of costly therapies within the scope of that given payment, it was at the cost of downstream complications.

When erythropoietin-stimulating agents use decreased as a cost-saving measure, mean hemoglobin concentrations decreased and the rate of red blood cell transfusions for dialysis patients in inpatient settings increased.

While care was provided efficiently within the bundle, this change led to an overall negative impact on patient outcomes.

- The financial limitations of bundled payments pose structural barriers against the adoption of innovative technologies

The ESRD population represents ~1 percent of all Medicare patients, yet represents 7 percent of FFS Medicare spend. As an outsized spend category, CMS has reason to both reduce spend and limit spend growth for ESRD patients.

Consequently, the CMS base bundled payment for CMS, $257.90 per treatment for 2022, has been unable to keep up with the increase in costs to provide dialysis. Clinic stakeholders (as well as independently conducted research) report that operating margins are in the single digits for Medicare patients, and that Commercial reimbursement is needed for clinics to maintain sustainable profitability.

Innovative technologies have the potential to decrease the cost to care for dialysis patients, but they also require upfront costs for adoption, which may not be feasible for clinics and dialysis organizations.

Finally, bundled payments have the potential to incentivize corner-cutting and substandard care. In the most extreme cases, providers may be compelled to ration care for cost reasons or to use poor quality resources all in an effort to reduce costs.

Improving on bundled payments: Ties to quality

In an effort to compensate for some of the negative ways bundled payments may still affect clinical practice, payers have begun tying payments to both clinical and financial measures of value.

Common clinical measures across diseases include hospitalization rates, infection rates, and readmission rates. Other clinical measures may be specific to a given therapeutic area or modality. For example, measurement of a provider’s adherence to a treatment pathway may be measured in oncology, while a measure such as HbA1c will, naturally, be specific to diabetes.

In general, payers are interested in metrics which are tied to downstream costs. In this sense, clinical metrics are also financial measures, to the extent that complications and adverse events cause additional costs which must ultimately be borne by the payer.

The Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network (HCP-LAN) has described three broad ways these metrics can be applied to payments a provider receives. Each subsequent method increases the amount of financial risk providers assume, as well as the amount of technological, operational, and organizational complexity required for successful operation:

1. Pay for performance

Payers and providers agree on an outcome metric, some measure of success, and a negotiated bonus structure if the providers “succeed”. For example, a provider may be held to a 5 percent reduction in hospitalizations or hypoglycemic events for a diabetic population.

Similarly, a nursing care facility in Georgia, which receives Medicaid reimbursement, is eligible as of June for an up to 4 percent “quality incentive adjustment”. This is only applicable if they are above the state average in various quality metrics (such as percentage of residents who received a flu vaccine), or if they receive an ACHA Silver/Gold award or accreditation from The Joint Commission.

In an industry where pre-pandemic operating margins for Medicaid patients were on average -3 percent, a 4 percent reimbursement adjustment can be significant. Variations on this model also include penalties for poor performance, such as the well-known CMS penalties for hospital-acquired conditions or readmissions.

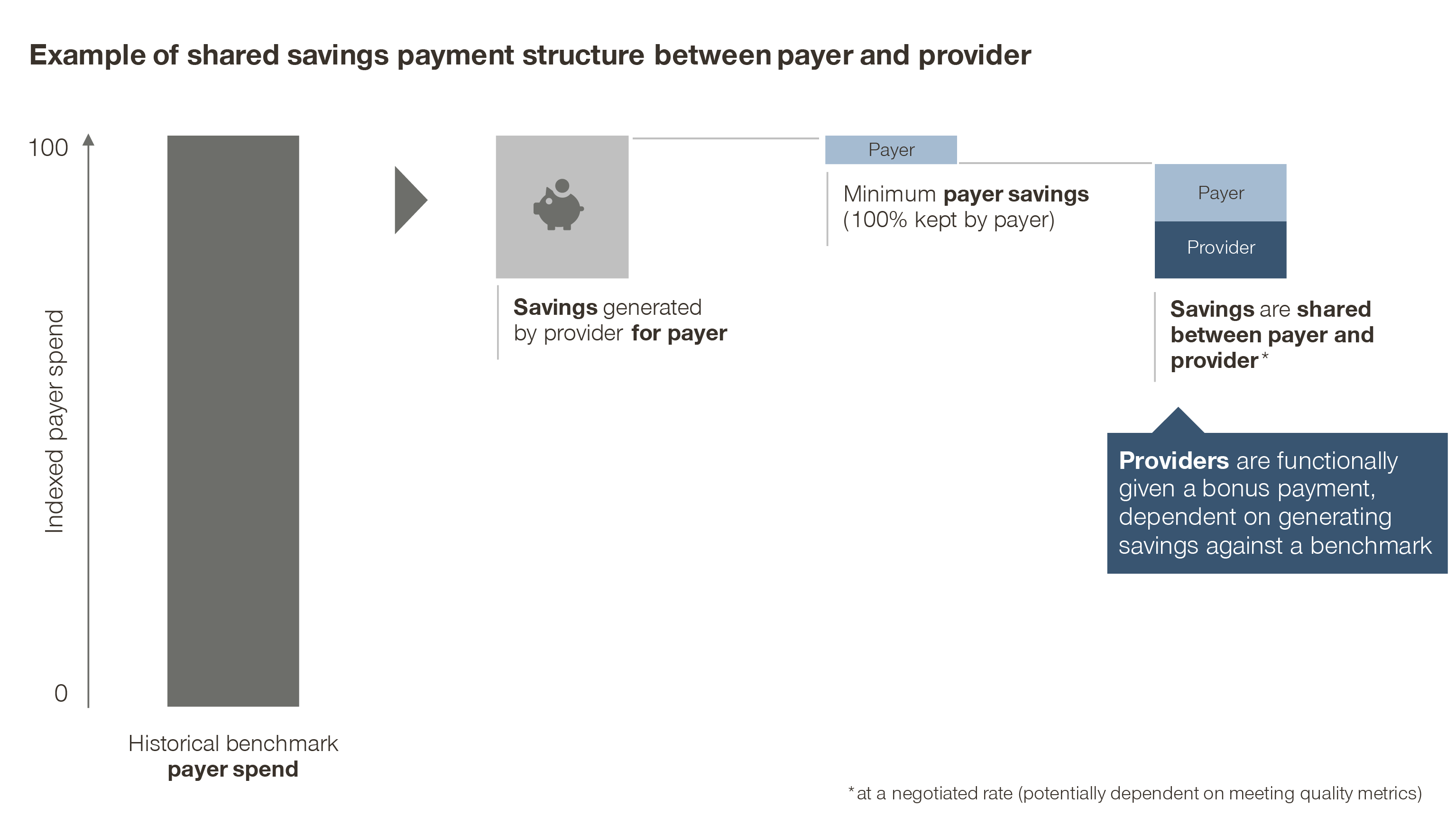

2. Shared savings

In this model, the payer defines a reasonably achievable cost reduction as a benchmark for the provider. Any additional savings beyond the benchmark are then shared between the two parties.

Functionally though, the provider simply receives a bonus payment: the hypothetical savings from avoided costs, measured against a predefined benchmark, which may be adjusted based on quality or patient outcomes.

Variations on this model include “shared risk” models, where the provider must bear some of the loss if they underperform the financial benchmark. This practice, however, has its drawbacks. It may put already poorly performing providers in further financial difficulties, as well as penalize low-volume providers for managing a panel of patients who, by chance, have a worse natural disease progression than average.

3. At-risk population-based reimbursement

The provider receives a fixed amount, typically either per episode of care or per patient per month. The provider is then responsible for keeping costs associated with both treatment and potential complications within the fixed payment.

In this way, the provider is also incentivized to maintain high clinical quality: to minimize complications is to save money, and the best way to minimize complications is to ensure high quality of care.

Risk-adjustment examples and factors to consider

There are of course many other factors which impact outcomes that are outside of the provider’s control, such as clinical preconditions: comorbidities, mental and behavioral health difficulties, medication and therapy adherence/compliance, and acuity level when the patient enters the provider’s care.

Sicker patients, will, on average, cost more to treat and have poorer outcomes. Providers should not be negatively impacted for taking on sicker patients, given that they can only control their clinical decision making and protocols. As a result, adjustments to base payments based on patient risk (either on an individual or aggregated basis) has become common to account for this.

An example of this is risk-adjustment for Medicare Advantage plans, where risk scores are calculated on an individual patient basis to determine the PMPM payment MA plans receive. This in itself has led to ethically questionable behavior, where providers are encouraged to “accurately” code patients to maximize the risk score and therefore payment from CMS.

Another example of risk adjustment is in CMS’s bundled payment structure for dialysis patients. The base payment is adjusted for a variety of factors: inflation, patient characteristics (age, BSA, BMI, comorbidities, dialysis onset), and facility factors (patient volume, geographic wage index, and location).

Similarly, quality and outcome measurement can be adjusted to account for this too. The goal/target levels/reductions can be adjusted so that providers with sicker populations can meet less stringent targets to receive the same bonus, or can be expressed as improvements from a baseline, which controls for variations in population characteristics.

Additionally, in some indications, clinical value metrics have been difficult to define. For example in oncology, overall survival, as well as complete/partial response rates, remain as indicators of efficacy -- and therefore value -- for therapeutics.

However, new treatments may also have additional safety risks and increases in Grade 3/4 adverse events. Providers must make the complex decision to extend survival, weighed against the risk of serious side effects.

By considering safety, efficacy, and costs compared against other drugs in the space, evidence-based guidelines aim to provide insight into what defines a “high-value” therapeutic.

In the commercial space, some payer organizations additionally look to adopt clinical pathways. Physicians may be given incentives (for example, annual bonuses) to shift their treatment decisions towards evidence-backed high-value drugs.

To create these guides, a pathway committee composed of disease experts considers clinical evidence to develop a framework of preferred treatment options, focusing on maximizing patients’ lifespan while reducing unnecessary spend on avoidable complications.

To hold physicians accountable for delivering value, payers and physician organizations have moved to measure pathway adherence as a measure of care quality, rather than highly patient-dependent outcomes.

Patients, in aggregate, benefit from an improved treatment experience by reducing additional treatments needed, from both failed medications and adverse events that require further treatment.

It is important to note that pathways are not intended to replace physician judgement. In most cases, pathways do not include downside penalties for non-adherence, allowing physicians to prescribe “off-pathway” medications for unique clinical cases.

Recommendations for manufacturers

In response to these shifting incentives, providers as a group will slowly but surely begin to change their behavior. They will change how they organize and operate, how they care for patients, and how they evaluate new products which enter the market.

Specifically, providers’ overall concept of value will become more complex – no longer solely focused on clinical metrics, but also on a product’s ability to help them deliver on payers’ definition of value.

Manufacturers must anticipate these shifts and begin evaluating how to adjust strategies in response. Specifically, four key takeaways emerge:

1. Attaching quality and outcome measures to reimbursement, as well as a shift to bundled payments, frames very sharply to providers the implications of poor quality, inefficient, or unnecessarily costly care

To that end, how exactly a drug, device, or other product enables providers to perform better in value-based contracts with payers will underpin the value of the new technology.

Manufacturers should align value messaging and data generation/collection with payer requirements for providers, to enable providers to perform in their value-based contracts.

Consider including economic measures (e.g., downstream cost savings) in both clinical trial and real-world study designs. Under shared savings and at-risk models, any product which can demonstrate cost savings will, by definition, drive value for all stakeholders.

2. Payment structures will affect adoption of these innovations

In indications where bundled payments are prevalent and the shift to more advanced value-based constructs has not yet happened, bundled payments can limit innovation.

Pass-through subsidies, carved-out FFS reimbursements, and a subsequent adjustment to the bundled payment will be necessary to make adoption of new products financially viable for providers.

However, under a shared savings model, for example, innovative products which can demonstrate true clinical benefits and cost savings will have no issues with adoption. If a product can significantly reduce hospitalizations, payers will share some portion of the saved cost of that avoided hospitalization with the provider.

As long as the cost of the product is low enough to produce an acceptable ROI for the provider, adoption is simply like performance marketing or growth hacking for a SaaS business.

The truly innovative product would be self-sustaining: the more money invested in this product, the more savings are passed on by the payer. As a result, manufacturers may wish to align pricing with the reimbursement structures of the providers in a given specialty.

For specialties where value-based reimbursement is common, aligning pricing with the savings a provider generates can maximize upside value capture.

3. As payers relinquish utilization management and clinical decision making power to providers, the role especially of KOL organizations will increase

For example in oncology, establishing inclusion and early positioning on pathways, especially widespread guidelines like NCCN, will be increasingly important to maximize utilization.

Additional clinical data, like head-to-head trials or studies of use in earlier disease stages can generate evidence needed to establish favorable positions in a treatment algorithm. Real-world evidence is also an important driving factor -- a successful change in treatment in one clinic is likely to be replicated in others with similar patient mixes.

Shifts in reimbursement structures are not a silver bullet for the US healthcare system. Other issues, such as consolidation, price intransparency, cost shifting to Commercial payers, and poor data and coordination capabilities, must also be solved.

Nevertheless, a movement towards value-based reimbursement could spur innovation in other areas. Multi-specialty coordinated teams would emerge as reimbursement evolves to encompass multiple settings of care. Significant industry-wide investment in automated data collection, cleaning, analysis, and reporting capabilities are needed to successfully operationalize value-based contracts.

Ultimately, all these shifts are related to each other and must move in tandem: improvements in one area can spur and make necessary improvements across all other areas.

By planning for the above, manufacturers can be well-prepared to demonstrate an increasingly complicated concept of value to providers and succeed in an ever-evolving healthcare system.